The Takeover of Teacher Appraisals

This NORRAG Highlights is contributed by William C. Smith, Teaching Fellow in Comparative Education and International Development at the University of Edinburgh, Moray House School of Education. In this post, the second of a three part series, the author shares some of his recent work on test-based accountability for teachers. Using data from the 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), he draws attention to the disappearance of teacher appraisals as a formative tool and the detrimental effect this transition has had for teachers’ engagement with feedback and their job satisfaction.

Teachers play a central role in a country’s education system. They are vital for student’s well-being and development, are the ‘street level bureaucrats’ responsible for the direct implementation of policy, and represent a substantial portion of the education budget.

The importance of teachers have often made them targets in the age of test-based accountability. The global transformation, shifting accountability from the central government to schools and teachers, has eroded trust in the teaching profession. Poor outcomes are often blamed on inadequate teachers. A negative story promoted and reinforced, at times, by the media – as seen in one-sided portrayals of teachers as lazy and incompetent in Australia, Bangladesh, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa.

The takeover of teacher appraisals is one illustration of the larger movement that hold teachers accountable for student performance. Historically, appraisals acted in a formative fashion, providing teachers with ongoing feedback to better their practice. This was distinct from teacher evaluations, which provided a final summation of teacher performance, often with high-stakes consequences. The supporting role of appraisals was kept separate from the oversight role of evaluations.

By the end of the 20th century, the two complimentary systems were clearly merging. Appraisals and evaluations are now often indistinguishable. This is clearly illustrated in the OECD’s Synergies for Better Learning report: the teacher appraisal “typically aims to support teachers’ professional development and/or career advancement, and also serves to hold teachers accountable for their practice” (p. 272, emphasis added). Skeptics pushed toward this evolution suggesting that appraisals were “superficial, capricious, and often don’t even directly address the quality of instruction much less measure students learning”. In 2000, Fullan and Mascall situated appraisals as “part of a political movement of accountability”, in which “teachers are seen as public servants and should be accountable for their work” (p. 41). High stakes, often linked to student test scores, had begun to infiltrate teacher appraisals.

High stakes are present when results are “tied to increases in salary, promotion, and maintenance of employment”. Across the 33 countries that participated in the 2013 TALIS, approximately four out of five teachers worked in schools that practiced high stakes teacher appraisals. Italy, Japan, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain were the only countries where less than 50% of teachers worked in schools that did not apply high stakes to appraisals.

Multi-metric accountability is an emerging consensus that promotes the use of multiple indicators when holding teachers accountable. Using a single measure would present a distorted image of the complex and multifaceted work done by teachers. In looking broadly at national trends, this approach appears to dominate. Sixty-three percent of teachers in the 2013 TALIS worked in an appraisal that included six components – student test scores, teacher observations, parent feedback, teacher’s content knowledge, student surveys, and teacher’s self-assessment. Across the entire sample, appraisals based solely on student test scores were only practiced in Brazil (0.47% of teachers) and Iceland (3.64% of teachers).

Still, just because multiple factors were included in appraisals does not mean the factors received equal emphasis. Student test scores were the most commonly used component in teacher appraisals (included for 97% of teachers) and when used for high-stakes purposes, 97.3% of appraisals were based, in part, on student test scores.

Student test scores or performance was clearly the focus of school leaders when discussing appraisal feedback with their teachers. Student performance was the most emphasized piece of feedback for teachers in 20 out of the 33 TALIS countries. In support of other research, England and the United States are most test obsessed. School leaders in these countries not only rank student performance approve all other topic when providing feedback but place a greater relative emphasis on it, compared to other countries.

Treating the appraisal system as a high-stakes evaluation has multiple negative consequences. When test scores were emphasized in appraisal feedback, teachers felt the feedback they received had little value. They were more likely to consider the appraisal process an administrative, box-checking exercise and less likely to consider it valuable for improving their instruction. Additionally, past studies have found that teachers are less likely to engage in their own practice and with others when feedback is understood as useless. In Flemish schools in Belgium, the perceived utility of feedback is one of the most powerful predictors of whether a teacher pursues professional development.

Teachers in test-based accountability systems are less satisfied with their work. They often suffer from increased levels of stress and anxiety, which can lead to burnout and increased teacher turnover. How teachers are evaluated can shape their level of satisfaction. Supportive evaluation practices have potential, with teachers reporting meaningful change in their practice and higher levels of satisfaction. Unfortunately, the possible benefits of teacher appraisal systems[i] are erased once a school testing culture is in place.

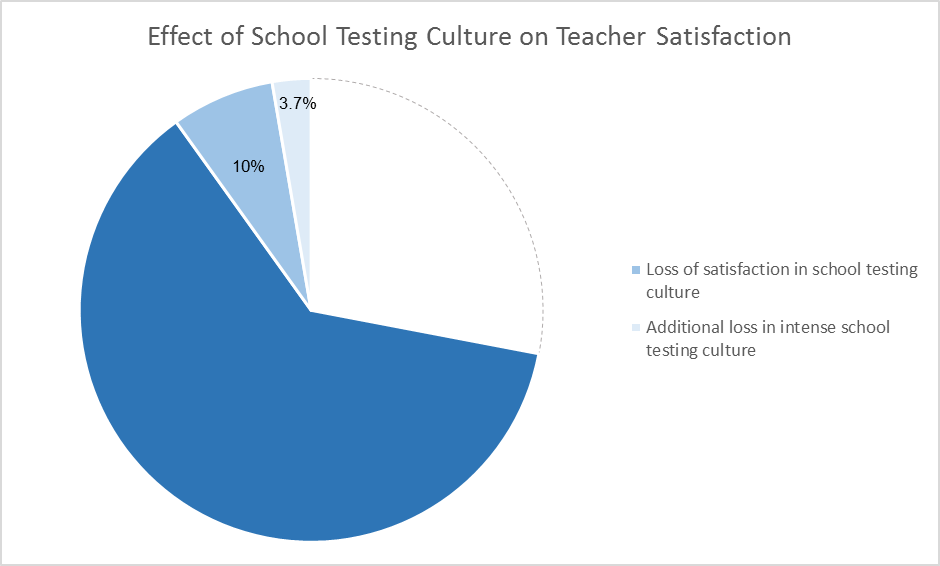

Teachers in an intense school testing culture – where test scores are included in the teacher’s appraisal and their principal regularly takes actions to ensure teachers feel responsible for their students learning outcomes – demonstrate lower levels of job satisfaction. The graph below illustrates how a school testing culture can chip away at the satisfaction of teachers. Teachers in schools that do not subscribe to a testing culture report a satisfaction level of about 72 on a 100-point scale. Compared to teachers not in a school testing culture, those working where appraisals include student test scores report satisfaction levels that are 10% lower. In the most intense school testing cultures, teachers are 13.7% less satisfied than those that do not operate under the spotlight of test-based accountability.

Motivated and satisfied teachers are essential in providing quality education for all. When their efforts are reduced to a test score, frustration ensues and anxiety and stress are compounded in a competitive environment that leaves many looking for a new line of work. Instead of working collectively with school leaders, colleagues, and families, teachers become the target of blame. To rebuff the current trend, the well-being and achievement of students needs to be understood as a shared responsibility with teachers acknowledged for their expertise as professionals and invited to the table in conversations on education reform.

[i] Smith & Holloway (2019) and the OECD’s Synergies for Better Learning both highlight the potential importance and benefits from a well-functioning, supportive appraisal system. In Smith & Holloway (2019), teachers that feel their appraisal had a positive impact on their teacher satisfaction are more likely to report higher levels of overall satisfaction. The benefits and results of the OECD’s report, however, are challenging to interpret given their analysis does not differentiate between the developmental (historically associated with appraisal) and accountability (historically associated with evaluation) functions of the appraisal. The importance of this omission is actually recognized in their report, which states “where the accountability function has taken precedence over the developmental function and the appraisal is mostly perceived as punitive, teacher appraisal may create a climate of tensions and fear” (p. 279). This blog and the work it is based on highlight the need for research that distinguishes further the purposes of teacher appraisals/evaluations and investigates the related effects.

Acknowledgements: This blog draws significantly from two pieces of research

- Smith, W.C. & Holloway, J. (2019). School testing culture and teacher satisfaction. Presented at the 2019 CIES Conference (April 14-18, 2019).

- Smith, W.C. & Kubacka, K. (2017). The emphasis of student test scores in teacher appraisal systems. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25(86).

About the author: William C. Smith is a Teaching Fellow in Comparative Education and International Development at the University of Edinburgh. He was previously a Senior Policy Analyst for UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report. His publications on education policy and international development include his edited book The Global Testing Culture: Shaping Education Policy, Perceptions, and Practice (2016, Symposium Books). Email: w.smith@ed.ac.uk

Editor’s Note: This post is part of a mini-series of posts that discuss issues pertinent to the global growth of accountability systems in education, its relevance to stakeholders and the challenges moving forward. Part I of the mini-series delves into the discourse around accountability as solution to the learning crisis worldwide; Part II examines teachers’ perspective to testing and accountability, and finally, Part III sums up the importance of multi-stakeholder structures in education policy-making and evaluation.

Contribute: The NORRAG Blog provides a platform for debate and ideas exchange for education stakeholders. Therefore if you would like to contribute to the discussion by writing your own blog post please visit our dedicated contribute page for detailed instructions on how to submit.

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s opinion, policy or activities.

Pingback : NORRAG – Structuring Democratic Voice to Improve Accountability in Education By William C. Smith & Aaron Benavot - NORRAG -