Reframing the Terms of Debate: From ‘International Architectures’ to Complex, Adaptive, and Multiple Forms of Organisation

This NORRAG Highlights contributed by Radhika Gorur, Associate Professor at Deakin University and Director of the Laboratory of International Assessment Studies, provides alternative ways of thinking with regards to Nick Burnett’s recently published essay on the international architecture for education and Steven Klees’ related blog post. Gorur reminds us that transformative work is time-consuming and that trust and awareness of the culture and the dynamic of communities have to be part of it. The author proposes a shift from a rather static architecture to a dynamic approach that takes the form of hybrid egalitarian networks which allow for dynamic relations, embracing “new power” thinking.

There is now serious concern that even the minimal goals of SDG4 are unlikely to be met. Various groups are calling for more funding, more data, more teachers, more training, more accountability – and for a rethink around what needs to be done and who needs to do it. Nick Burnett’s recent invited essay and Steven Klees’ response to that article are serious voices in these debates. But what are the terms within which these debates are taking place? What are the assumptions that lie beneath the analyses and the solutions? In this response to Burnett’s essay, I want to touch on some of these key concepts and premises, and propose some alternative lines of thinking.

From “international architecture” to complex, adaptive, and hybrid systems

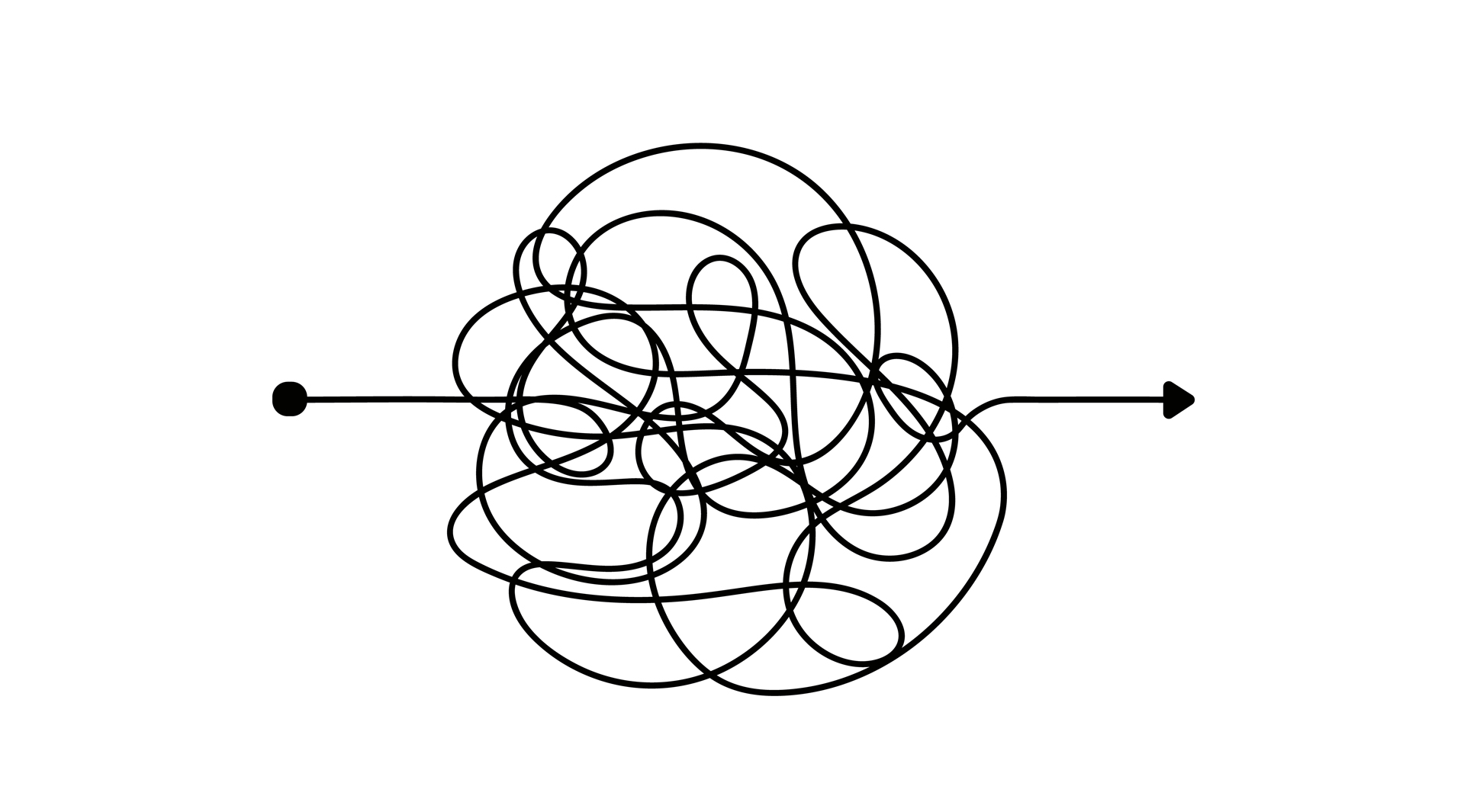

Burnett opens his essay with the provocative statement that “The international architecture for education is failing the world.” But what is this ‘international architecture’? In many ways, it is a figment that is only tentatively held together by declarations, high-level forums, reviews, standards, monitoring mechanisms, funding agreements, contracts and so on between a dizzying array of institutions and actors distributed throughout the world. Burnett’s vision of “a global institutional system that effectively supports national education systems to improve their performance” evokes the stable, stately, predictable and controlled ‘physics of big things’ – like planetary systems. But the ground realities – and not just in aid dependent nations – are more akin to the chaotic, unpredictable, counter-intuitive, frantic and complex movement that occurs at the quantum level. At the root of the problems raised by Burnett lies this issue: the principles that regulate the planets are being used to regulate the quantum level. And this same issue also arises in the solutions that Burnett proposes.

The concern that international aid is failing to deliver on its promise, and the search for strategies to make aid more effective are, of course, not new. One such strategy was inscribed into the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2005, in which 111 countries agreed to a “practical action-orientated roadmap to improve the quality of aid and its impact on development” organised around the five principles of “ownership, alignment, harmonization, managing for results, and mutual accountability.” This vision was operationalised by agreements to align the funding strategies of donors with the budgets of recipients. Burnett’s reiteration of the need for such alignment nearly 15 years after the Paris Declaration proves that this strategy has simply been spinning its wheels.

We have no right to be surprised that such an ambitious modernising project has failed. Such aspirations are seldom successful, and this is just as well, because when they are successful, they can have devastating effects, as James Scott (1998) has shown so powerfully in varied cases across the globe. Such projects require a tunnel vision – and such visions elide crucial specificities, often to the detriment of the most marginalised communities which become matters of concern. As Bowker and Star (2000) and others have amply demonstrated, the world is hybrid and complex – and attempts to create the kinds of global legibility, classifications, and accountability and monitoring systems that Burnett yearns for cannot be achieved without committing ontological violence. Such projects, premised on synoptic views, discount local knowledges and make demands that are often oppressive and ill-suited, and local actors struggle to find workarounds to deal with plans dreamed up elsewhere.

Burnett’s solution to the failing architecture is in part to restore the architecture by starting with a slightly scaled down core structure, and then gather the momentum to build from there. I propose that, fundamentally, architectural metaphors and dreams of Empire are ill-conceived, iniquitous, and most of all, unworkable. Following Urry (2004), I point to the advice of the Gulbenkian Commission on the Restructuring of the Social Sciences, which emphasized the importance of conceptualizing both the natural and the social sciences as characterized by complexity. A new way of working is needed, ‘based on the dynamics of non-equilibria, with its emphasis on multiple futures, bifurcation and choice, historical dependence, and … intrinsic and inherent uncertainty’ (Wallerstein 1996, p. 61, cited in Urry, 2004).

This shift to complexity thinking means not drawing up an ultimate global organisational chart with clearly defined roles, and not preparing reductionist KPIs and pre-determined goals for monitoring and accountability. Instead, plans are premised on systems that are adaptive, evolving and self-organising, like ‘walking through a maze whose walls rearrange themselves as one walks’ (Urry, 2004, p. 111).

Perhaps it may be more useful to imagine other metaphors – such as ‘infrastructures’ or ‘hybrid, egalitarian networks’ as alternatives to the rather static ‘architecture,’ which is limited in the tension it can tolerate. Infrastructures are more basic – and they allow a range of different structures, tailored to local and regional situations, to be generated. But perhaps these, too, are too deterministic. Hybrid, egalitarian networks (as opposed to ‘aristocratic networks’ (Buchanan, 2002)) envision collaborative engagements among various partners in dynamic relations, where the system is not set once and for all, but is flexible, intelligent (in that it adapts) and emergent.

Old power, new power and scale

Another way to think about this is to use the distinction made by Heiman and Timms (2018) between ‘old power’, which acts like currency and is therefore hoarded, centralised and treated like a possession, and new power, which is open, participatory, peer-driven, and acts like a current (see also Gorur, 2019). They illustrate this distinction by contrasting Harvey Weinstein’s ‘old power’ approach, which sought to gather and wield power to control others’ fates, with the approach of the #MeToo movement, which derived its power from peer-to-peer movement and manifested itself in many different ways – as Facebook communities, law suits, meetings over coffee and so on. There was no single leader controlling and monitoring others – rather, various groups and individuals took up the hashtag and made it their own in different ways.

In new power thinking, ‘global’ does not mean a single vision, a single agenda, or, more grandly, a single ‘system’ or ‘architecture’. Rather, scale is achieved when a basic idea, such as exposing abuse, is allowed to take on different forms, as per the desires and motivations of different groups. The recent protests in Hong Kong provide another example – it appears to have no identifiable leader, no formal system or hierarchy, no plans that are made in advance. Rather, the mob organises itself through informal means minute by minute, and has managed to mobilise large masses of highly committed people.

Whilst I am not suggesting that this kind of ad hoc-ness is possible or even desirable in education aid, what I am suggesting is that grand, controlling visions may not function as well as more hybrid, local and emergent approaches might.

Linked to the above is the danger of a single story, as Chimananda Achebe argues. Burnett’s vision of one global agenda, one single ambition, with the whole world’s support, assumes that UNESCO’s vision of what ‘quality education’ should look like, which is linked to the assumed purposes of education, is self-evident, apolitical, and universal. Some would argue, however, that this vision arises from a destructive form of capitalism that has produced a consumerist society that is effectively destroying the earth at an irreversible pace (see Klees, 2019).

Why do poor policy ideas persist?

The question, for me, is not so much why the global architecture has failed (it is an unrealisable dream), or how to fix it, as much as how it is that poor policy ideas (such as developing a strong ‘international architecture’) persist, and how they manage to mobilise such large numbers of institutions, individuals, money and material. The global imaginary, and contemporary affordances like the ability to look up any document within seconds, to cut and paste, to access a group of policy entrepreneurs and consultants who are on everyone’s ‘must have’ lists – all these promote an ‘echo chamber’ effect – a kind of self-referential hall of mirrors. Formal declarations like the Paris Declaration that seek to align and harmonise only serve to intensify these practices – alternatives are frowned upon, strays are reigned in and everyone is disciplined into marching to the same beat – at least on paper. Instead of weeding out poor ideas, attempts are made to make those ideas more ‘robust’, bringing together and committing yet more actors and yet more resources to the same idea, and making yet more resolutions and promises.

Paradoxically, accountability practices often serve to perpetuate rather than identify and stop poor policies. Once an idea is adopted, it is unlikely to be declared a failure and given up in favour of an alternative – particularly if a strong pitch was made to persuade donors to part with a big sum of money. In any case, it is often difficult to isolate what precisely is not working. The effects of policies often take very long to be manifested in statistically significant ways, and evaluations are demanded long before these effects might materialise. The ritual of external evaluation, the formats of such evaluation reports, the pressure to demonstrate success to funders – all these make for sanitised reports where even failures are made to sound like successes. Often the focus of recommendations is not the idea itself, but its implementation. Not only does the idea continue to remain in circulation, sooner or later it gets adopted by someone else through the contagion effect.

Small worlds, co-presence, conversations, and three cups of tea

The key to begin rethinking education reform and making progress towards the aspirations of SDG4 is contained in the first paragraph of Burnett’s essay, where he declares: “the major debates are increasingly irrelevant and divorced from reality on the ground.” Dismissing certain debates as ‘irrelevant’ may be the reason why the efforts of international agencies do not work ‘on the ground’. In Burnett’s ‘aristocratic network’ or ‘international architecture’ model, action is controlled by a single global leader peering down at the world from a lofty perch – a puppeteer pulling strings on a ground that is barely visible for being so far away.

Scott’s description of what is left out when a synoptic view is prioritised serves as a wonderful analogy – and as caution. He says that, viewed through a fiscal lens which transforms ‘nature’ into a ‘natural resource,’ all that becomes visible of a varied, diverse, thriving forest is the fiscally relevant timber. Absent from these reckonings are the firewood, berries, roots, medicinal plants, game etc. as well as the villagers nearby who depend on these gifts from the forest (Scott, 1998; Gorur, 2016).

In the reconceptualised hybrid, egalitarian, fluid networks, debates are not dismissed as irrelevant – instead, the emphasis is on “co-presence, conversations, meetingness, travel” which facilitate a very different way of engaging, prioritising, planning and implementing (Urry, 2004, p. 124). It would mean that the seemingly inexhaustible list of agencies, institutions, foundations and other organisations involved in global and regional education reform are not organised vertically, along a ladder that descends from a pinnacle of power, but are deployed horizontally, on the ground, working with, rather than on, the communities they wish to reform – in relations of mutual learning. This kind of ethnographic engagement would put paid to some of the key solutions Burnett raises, such as involving private actors (like Klees, I shudder at this thought) and calling for more systematic reviews to find out what works (no global number crunching can show what techniques ‘work’ to improve education outcomes when war or famine or poverty are the chief issues confronting schools).

Adopting a dynamic approach rather than of implementing pre-formulated plans would bring about a paradigm shift in development and aid thinking, forcing a confrontation with ‘the contradictions and contingencies of practice and the plurality of perspectives’ (Mosse, 2006, p. 938) and decentering the ‘postulated omnipotence of the global whether it be international capital, neoliberal politics, space flows, or mass culture’ (Burawoy, 1998, p. 30).

Even more simply, perhaps the answer lies in the explanation given by the village chief to Greg Mortenson when he was lost in the remote mountain village of Pakistan:

Here, we drink three cups of tea to do business; the first you are a stranger, the second you become a friend, and the third, you join our family, and for our family we are prepared to do anything—even die.

Transformative work requires time, patience, trust, mutual respect and learning, an awareness of the culture and the dynamic of communities. However powerful and well-funded, however well-armed with a priori knowledge of ‘what works’ based on systematic reviews, it is through drinking three cups of tea that change is made possible.

About the author: Radhika Gorur is an Associate Professor at Deakin University and a Director of the Laboratory of International Assessment Studies. Her research interests include education policy, regulation and reform; global networks, aid and development; data infrastructures and data cultures; classroom research; science and technology studies, and the sociology of knowledge. Email: radhika.gorur@deakin.edu.au

Author’s Acknowledgements: This post was made possible by a grant (DE170700460) from the Australian Research Council.

Editor’s Note: This post is part of a public dialogue mini-series of posts in relation to emerging topics on the international architecture for education. If you are an author(s) and wish to respond to this mini-series, please email your contribution to blog@norrag.org Submission guidelines can be found here: https://www.norrag.eight-id.com/contribute/

Contribute: The NORRAG Blog provides a platform for debate and ideas exchange for education stakeholders. Therefore if you would like to contribute to the discussion by writing your own blog post please visit our dedicated contribute page for detailed instructions on how to submit.

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s opinion, policy or activities.

I enjoyed the piece. You cover quite a range of ideas which is always fun. We live in a world of dots, all of which can be joined, perhaps some kicking and screaming.

The distinction you make reminds me or the argument Howard Becker makes in What about Mozart? What about murder? : reasoning from cases. He distinguishes between a nuclear physics model, a social science theory of everything, and one based more on a physiology model in which local variation is an important component.

Quoting Becker:

“The standard model, the law-seeking model, taking experimental science as its model, supposes that social organization exhibits deep regularities, that certain forms of collective action take the same basic form, and that careful measurement of indices of those regularities will reveal the laws that produce them. It isolates variables, measures them, and demonstrates their regular association with each other, expecting that a small number of variables will suffice to explain most of the variation in the independent variables being investigated.

My informal exploration followed a different model, based on a different logic. This model recognizes that there will never be enough variables to explain all the variation in any specific situation, but it doesn’t want to miss any that operate in the situation we’re interested in and affect what happens there. It uses cases to find more variables. It tries to do two things more or less simultaneously: understand the specific case well enough to know how it ended up happening the way it did, and at the same time find things to look for in other cases that resemble it in some ways, even though they differ in others. ”

So there is work to reduce complexity, smooth things over, find “what works (everywhere), or work to embrace the complexity and to continue to puzzle more over it, which I think is an indicator of good research, asking better questions.

In both models however, laws can be still seen to be present. In one, they are given, as in the standard model in physics, in the other we are still formulating, hypothesising and testing them as well as exploring their inter-relations. The early computational explorations of complexity were derived from the use of very simple equations (laws if you like) that produced complex outcomes. Via an ever increasing set of new and emerging fields of human inquiry, the world is increasingly being understood in terms of multitudes of interacting (networked) complex systems some of which can be glimpsed by using large amounts of computing to identify patterns.

Framing education as a set of practices that can be simplified, understood and easily managed takes us back to an era that has been over written by decades of digital developments. These developments show no signs of slowing down, stabilising or being domesticated. Those who advocate for this framing evidence a certainty which was once well characterised by Henry Kissinger: “To be absolutely certain about something, one must know everything or nothing about it.”

Perhaps if education is framed more akin to research, i.e. it is puzzling, uncertain, risky, surprising and concerned more with questions than “correct” answers, we may be able to move forward in supporting the young to better research the mess our generation has left them. 🙂

Hi Chris – what a lovely response. The idea of forcing dots to join, even as they protest – is evocative and amusing – even if it might be a comment on my possibly ill-advised attempt to do so! I am getting increasingly exercised about the way we are approaching the global reform agenda – both as the ‘doers’ and as ‘critics of the doers’ – hope we manage to do a little bit better over the coming years – so much depends on it. I think with the aid stuff – it is not ‘education’ that is the issue as much as ‘reform’ and ‘aid administration’ and ‘governance’ – the ‘education’ issues about teaching and learning are almost the least of the issues . It’s more about the kids that are not in school, about the kids coming to school hungry or dropping out because they don’t have the opportunity to continue or because schooling is not giving them anything etc. It is not the finer points about increases in test scores – we are a long way from that for many children in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Have a look at this and tell me what you think…

https://www.ukfiet.org/2019/a-learning-crisis-or-a-data-crisis-rethinking-global-metrics/

And thank for goading me into blogging – except it took me so many years to get started!

Pingback : Link In Bio Instagram