University League Tables and Quality: What counts?

This NORRAG Highlights is contributed by William C. Smith (a Senior Lecturer in Education and International Development at the University of Edinburgh) and Antonia Voigt (MSc candidate in Comparative Education and International Development at the University of Edinburgh). According to the authors, the conventional university rankings are diverting universities’ attention away from quality to commercial interests whereas, the ‘THE Impact rankings’ redefine quality and leadership by highlighting social conscious institutions that are committed to environment and sustainable development, and leadership as responsible global citizens.

We react to rankings. Whether done at the local level – ranking schools in the community – or at the global level – ranking countries or institutions, the resulting league tables shape the actions of families, education leaders, and policy makers. What remains contested is whether such rankings capture quality in education and if so, quality according to who and for whom. If rankings are inevitable (still an open question), and they shape behaviour, it is critical we ask which behaviour is being motivated. Set apart from conventional university rankings, the THE Impact rankings demonstrate how an alternate view of education ‘quality’ can shake our embedded understanding of top tier Higher Education Institutions (HEIs).

A Limited, Commercially-driven Definition of Quality

Ranking systems were initially designed to help students make better informed decisions on their education and as a result optimise resources and quality in universities. Over the past two decades, popular university ranking systems such as ARWU, THE and QS have established themselves. Through assessing universities’ three core functions of research, teaching and internationalization, they aim to establish which institutions offer the ‘best’ quality. However, can quality, a context-dependent, multi-faceted and continuous process, be captured through this narrowly defined combination of immediate output and input metrics?

Since the late 20th century, the marketization of the global HE sector has become more obvious and university league tables contribute to and reflect this process. While claiming to measure quality, they are arguably rather portraying a university’s halo – its reputation, financial sustainability, and age. Motivated by the ideal of becoming ‘world-class’, universities, particularly Anglo-American ones, adopt ranking indicators from global ranking systems into their mission statements to align more with what is being measured. This has led to universities paying particular attention to research outputs and high fee-paying students, which reflect the increasingly more important monetary interests of universities. Rather than ranking systems adjusting to reflect more accurately what universities achieve, universities are adjusting to ranking systems to score better. This is a prime example of the cobra effect; the solution is making the situation worse. Ranking systems were supposed to optimise quality in universities but now they are diverting universities’ attention away from quality to commercial interests. This pursuit of commercial interests contributes to the convergence of universities’ understanding of quality towards a single, commercially-driven definition.

A Sustainable Development-driven Definition of Quality

Universities are integral components of 21st century societies. Often undervalued and underemphasised is their contribution as centres for global citizenship creation. They are leaders in international knowledge creation and exchange and sit at the nexus of governmental, public, and private interests. They have a responsibility to be forward looking, working for the benefit of their local and global community. If ranking systems are here to stay, can they be used to redirect attention beyond the commercial definitions of quality and re-elevate the public goods purpose of HEIs?

This is where the THE Impact ranking system comes in. This new ranking system has taken the key issue of our planet and the sustainability of economic and social development represented through the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as the basis for its rankings. The 17 SDGs – such as reducing inequalities, clean energy, decent work and economic growth, and climate action – are of global, political, social, environmental, and economic significance to which almost all countries worldwide have pledged commitment. They arguably embody the strongest and most widely recognised values of social leadership and global citizenship across nations and cultures. While the THE conventional rankings reduce universities to what happens in or just outside the lecture hall and in research, the THE Impact considers the multi-layered roles of HEIs. It assesses how HEIs contribute to the individual SDGs through their research, stewardship of resources, outreach in their local, national and international communities, and teaching. Universities can submit data for as many SDGs as they wish but have to submit data for SDG17 ‘Partnerships for the Goal’ to be included in the rankings, as alliances are fundamental to achieve the SDGs. The final score of institutions is calculated based on their research, stewardship, outreach and teaching in SDG 17 along with the three SDGs for which they have scored the highest.

THE World University versus THE Impact Top Performers

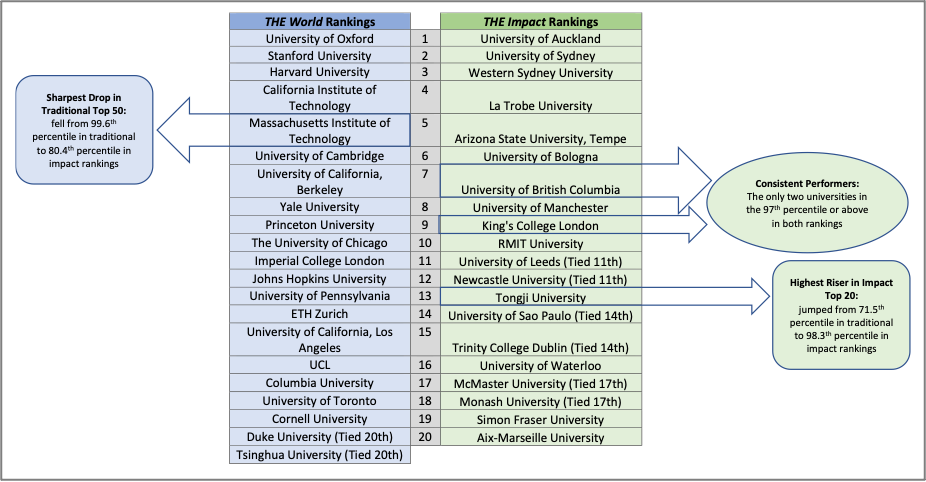

A comparison between the popular THE World University rankings and the new THE Impact rankings is challenging for two main reasons. In the 2020 rankings, the THE World University rankings assessed over 1500 while the Impact rankings compared only 768. In addition, there is only a small percentage of universities appearing in both league tables –10% of the top 20 and just under 20% of the top 50 in the traditional ranking appear in the THE Impact ranking. Given the different number of participants it is important to look at both the absolute and relative or percentile rankings of participating HEIs. Although only two years into its existence, the table below points to the potential of the THE Impact ranking in altering our perceptions of institutions seen as top performers. This may be in part because some of the common leaders of the THE World University league table – a group of well-known American and British universities including Harvard, Stanford, Oxford and Cambridge – are missing in the Impact rankings.

The absence of these ‘world-class’ institutions could be due to a number of reasons ranging from them deciding not to participate to their desire to maintain their halo, which could be tainted by a poor performance in the Impact rankings. If they were to participate, it is unclear if they would be able climb to the top in this league table too. They may, however, have some university features which could boost their chance. While it is too early to identify a specific set of university features which top performers in the Impact rankings share, there appear to be some similarities. Thus far, English-speaking and research-intensive universities in the Global North are dominating – only four in top 20 come from non-English-speaking countries of which are two are BRIC and two central European countries. These features mirror largely those of the leaders in the conventional ranking systems: research-intensive and English-speaking and sitting in the strong socio-economic context of America and Britain. Therefore, they may be as fortunate as the University of Edinburgh – usually in the top 30 in THE, QS and ARWU – which maintained its absolute position (30th in both the THE World and Impact rankings) while seeing minimal changes in its relative position (THE World – 98th percentile; THE Impact – 96th percentile). Or they may share the fate of the Massachusetts Institute for Technology (MIT). MIT – usually in the top 5 – failed to make it into the top 100 in the Impact rankings.

Many new universities are found at the top of the THE Impact league tables. While nine of the top 20 institutions in the THE Impact rankings are also in the top 150 of universities in the THE World rankings, some institutions are relative unknowns at the global level. For example, Aix-Marseille University and Tongii University are in the top 20 of the THE Impact rankings despite not being among the top 350 HEIs in the THE World rankings. The dramatic rise of some institutions illustrates how this new ranking system creates opportunities for social and environmentally conscious universities to make their mark. It gives them recognition for their commitment to the environment and sustainable development, and leadership as responsible global citizens – aspects of universities and quality which have been largely forgotten or unrecognized.

Since conventional rankings have been shown to shape universities’ behaviour and priorities towards commercial interests, could the Impact rankings shape behaviour towards sustainability? Should universities re-orient their activities to better ensure the longevity of our planet? Can public benefits take a more central position in not just the mission statements but the actions of institutions? Will universities match their push towards excellence with an emphasis on equity? The powerful, well-resourced universities that tend to dominate conventional rankings can make a difference. The THE Impact rankings could challenge these top tier universities to turn their attention away from routines that have helped secure their reputation and toward pursuits that prioritize our collective future. Those with the means to act have the responsibility to act. The transformation may already be taking place, yet without sharing their experiences publicly and participating in initiatives like the THE Impact rankings, evidence supporting institutional commitments is lacking.

Concluding Remarks

The THE Impact rankings are still in its early years and were initially developed to measure aspects of universities’ work which are overlooked by conventional ranking systems. Initial results suggest that the THE Impact rankings may force us to re-examine our understanding of top tier universities, redefining quality and leadership in the higher education sector by highlighting social conscious institutions that better direct resources toward creating a sustainable planet.

Acknowledgement: This blog draws significantly from: Voigt, A. (2020). Educational Quality, University Strategies and League Tables: A Case Study of the British North Preston University. [Unpublished Dissertation]. Moray House School of Education and Sport. University of Edinburgh.

About the authors: William C. Smith, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer in Education and International Development and Academic Lead for the Data for Children Collaborative with UNICEF at the University of Edinburgh. His recent research looks the perception of testing and other learning metrics as measures of quality and is best captured in his edited book, The Global Testing Culture: Shaping Education Policy, Perceptions, and Practice. Email: w.smith@ed.ac.uk Antonia Voigt is about to complete her MSc in Comparative Education and International Development from the University of Edinburgh. Her main research interests lie in the areas of higher education, league tables and university strategies. Email: antonia-voigt@outlook.com

Contribute: The NORRAG Blog provides a platform for debate and ideas exchange for education stakeholders. Therefore, if you would like to contribute to the discussion by writing your own blog post please visit our dedicated contribute page for detailed instructions on how to submit.

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s opinion, policy or activities.