Teachers, peace and social cohesion in Somalia: challenges and prospects

In this blog post, part of the NORRAG Blog Series on the Role of Quality Education in Building Just and Sustainable Peace, Aditi Desai and the co-authors* focus on social cohesion in relation to teacher beliefs, teaching practices and professional development experiences in Somalia. The authors argue that professional support and development opportunities for teachers are necessary to ensure socially cohesive and inclusive teaching practices in fragile contexts.

Introduction

Of the 65 million people living in forced displacement, almost 1 percent of the world’s population[1], nearly 41 million people-have been displaced within the borders of their own country, facing multiple humanitarian challenges. These include, ‘limited access to health and education services as well as economic and social marginalization’, a situation unlikely to exacerbate in the absence of durable solutions. (OCHA, 2017, p.13)

Of those displaced it is estimated over 17 million were children[2], where the nature of crisis and fragility is one of ‘increasing scale and complexity…in a globalized world’ and increasingly there is a ‘recognition that it is both a humanitarian and a development challenge’[3]. Dealing with displacement at present focuses on bridging ‘humanitarian action, development, peace, and security amidst protracted global displacement’ (Mendenhall, 2019, p.82)[4]

In the humanitarian-development-peace nexus approach and in the context of SDGs commitment to equitable and quality education, education brings ‘significant economic, social and health benefits’ but also fosters ‘cohesive societies … a vital tool in fighting prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination’[5]. Schools are safe spaces where children can avoid the worst effects of fragility and conflict while also potentially addressing some ‘causes of displacement’ and preventing future crises[6].

In contexts of conflict and fragility, teachers can promote peace, social cohesion and mitigate violence. They enable and support learners to navigate uncertain and complex future. However, their role is complex as they themselves have experienced displacement, trauma and professional insecurities. (INEE 2019; Winthrop & Kirk, 2007; Dryden-Petersen, 2017; Sayed & Novelli, 2016):

While teaching and learning must address cognitive skills, it must also offer opportunities for learners to heal from displacement or migration trauma, conflict and uncertainty. But in spite of the recognition of these needs, in-depth studies which capture teaching-learning experiences from the perspectives of teachers and learners remain few (IDMC, 2020)[7]. This is a significant gap given that experiences of displacement and fragility are context specific (IDMC, 2020). We will address this identified gap through the present blog.

This blog draws from data collected during the 2020-2021 school year on the nature and availability of CPD opportunities for teachers, their experiences with CPD and their identified needs[8]. It discusses these in terms of what teachers believe, they do and what they feel about their professional development, framed within a broadened understanding of education quality and social justice.

- Context: Puntland State, Somalia

Since 1991, three decades of conflict, insecurity and drought have left an estimated 2.9 million Somalis internally displaced,[9] the majority of whom have settled in over 2400 + IDP sites in urban and peri-urban areas across the country[10]. As 85% of these sites are informal settlements, IDPs find themselves in precarious conditions.

The civil war erupting in 1988 and the collapse of the central government in 1991 severely damaged social services in Somalia, including the education sector. An estimated 80% of Somalia’s scholars and teachers have fled since the outbreak of civil war (Lindley, 2008).[11]

During the conflict and post-conflict period, education was primarily provided privately. In the post-conflict context, a notable feature of education has been the concentration of professional, experienced teachers at larger schools, typically located in main towns, with comparatively lesser experienced or unskilled teachers operating in IDP schools.

The education administration in Somalia is divided between three main administrative units: the Ministry of Education, Culture and Higher Education in the FGS; MoEHE in Puntland State; and the Ministry of Education and Higher Studies in Somaliland. Additionally, the system is highly fragmented and poorly regulated ‘with inconsistent quality standards; curriculum and learning materials.[12]

While aid for education initially increased at the start of the recent decade, a pronounced decrease over the last three years is evident.[13] For example, the United Kingdom, Somalia’s second-largest donor, cut its funding by 60% in 2021.[14]

- Findings

- What do teachers believe?

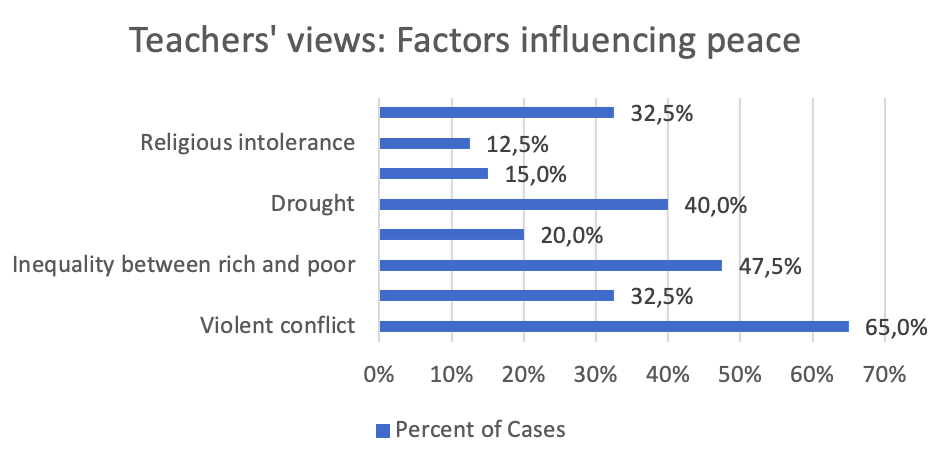

Factors influencing peace

For teachers, structural determinants of inequality, conflict, drought and clan relations were aspects constraining the achievement of durable peace in their specific contexts. Religious intolerance was cited least frequently as a factor influencing how peacefully people lived together. This relates directly with the experiences of IDP communities and the reasons why they have been displaced within Somalia.

Figure 1: Views on factors influencing peace

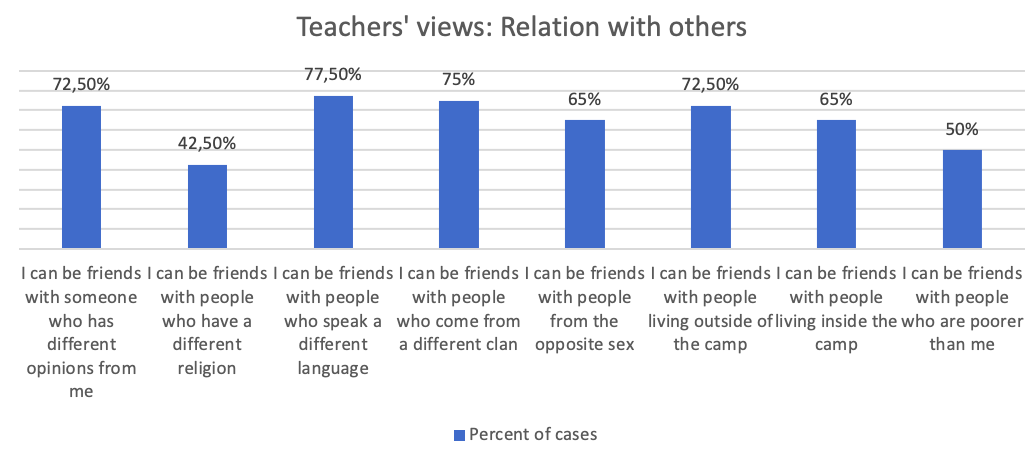

Relations with others

We asked teachers how they viewed relations with those around them. Teacher responses indicated their belief that they could be friends with people from different clans, ethnicities or linguistic backgrounds. The selection of ‘language clan’ and ‘engaging with those outside the camps’ as positive suggest that teachers are positively disposed towards tolerance and respect, supporting the necessary through not sufficient conditions for durable peace. This also suggests that teachers’ views hold a promise for overcoming those very factors that militate against peace. However, being friends with people from another religion was cited least frequently as an aid to peace (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Teachers’ views on relations with others

- What do teachers do?

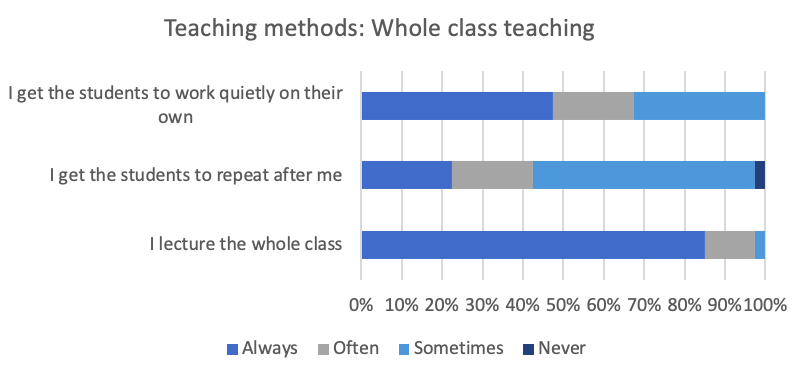

We asked teachers to report on their teaching practices and strategies for teaching mathematics and language in an effort to see how they incorporated social cohesion and equity while designing classroom learning experiences.

Overall, teacher responses suggest that teachers struggle to translate their stated beliefs into teaching practices. For instance, responses indicate that the most common teaching strategy is class lecture, confirmed by classroom observations.

Figure 3: Whole class teaching

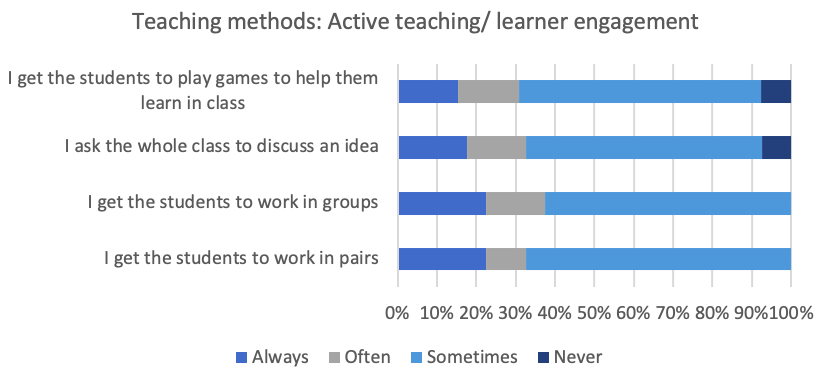

We asked teachers to rate how often they relied on various forms of active teaching to engage learners. Most teachers admitted to only occasionally requiring learners to work collaboratively, sometimes using games to teach, only sometimes supporting active learning (Figure 4)).

Figure 4: Active teaching/learner engagement

When asked how they promoted equity and inclusion in their teaching, by far the most common response was equal representation of both and girls in lesson examples. This was followed by asking both boys and girls to answer questions in class. And while differentiating tasks for learners according to abilities was also noted, at least nine teachers claimed to never do this.

As with the discrepancy between claims and actual practice for active learning, equality may not easily translate into classroom practices either. But teachers confirmed a positive disposition about adopting equitable practices to counteract the difficult socio-material realities of their learners:

We treat students who have learning difficulties unlike other students. We give them special attention and give them extra and specialized assignment. We give them special classes on Thursdays or Fridays. (School 8, Maths teacher interview, 2019-2020)

When I spot a distressed learner, I talk to them and ask what is bothering them. For example, there were two girls and their brother in the school….During the term examination their mother had a stroke and all of sudden passed away. This distressing and difficult situation led them to decide to leave the school. I advised against their decision and promised that we will support them, provide necessary materials that the school required, such as books. We promised that we will give them extra time and support to catch up rest of the students until this difficult time passes and they become mentally become stable. They agreed. (School 9, Social Studies teacher Interview, 2019-2020)

Teachers were asked to share how they made teaching relevant and contextualized. Responses indicated that while teachers made learning practical, this did not always link to the learners’ cultures.

It is important to bear in mind that teachers expressed dissatisfaction with the teaching and learning materials, as this inadequacy prohibits the design of more equitable learning experiences for learners.

The hardest part of my job is the lack of teaching materials. I find it difficult to visually show the students objects that represent the words I am teaching them. …I found that just to draw the letter “B” on the blackboard will not be enough to help the learners remember the letter, without some sort of picture representation. All we have in class are blackboard and white chalk. (School 9, Language teacher interview,2019-2020)

Some of the IDP school classrooms are way overcrowded for example in Grade 1. The class is designed to accommodate 25 students; however, it currently hosts more than 50 students. This makes teaching difficult. (School 9, Language teacher Interview, 2019-2020)

- What professional development support do teachers receive?

Systematic, regular and quality CPD opportunities are vital to provide teachers an opportunity to critically evaluate their own beliefs and to collaborate with colleagues to design more inclusive teaching practices. In light of this, we have tried to understand the CPD experiences and opportunities available for the surveyed teachers.

Overall, CPD opportunities were not evenly available to all 40 teachers surveyed or across all subject areas. In fact, only 17 of the 40 teachers reported receiving CPD in the previous academic year. Even within each school, interviews confirmed that not all subject teachers had opportunities to attend CDP training. However, all who attended a CPD training felt that they were valuable, practical for classrooms, and largely based on identified needs. But Teachers reported that the CPDs for inclusion and equity in the classroom were less beneficial although the training covered better subject knowledge, use of assessments, teaching difficult topics and incorporating group work.

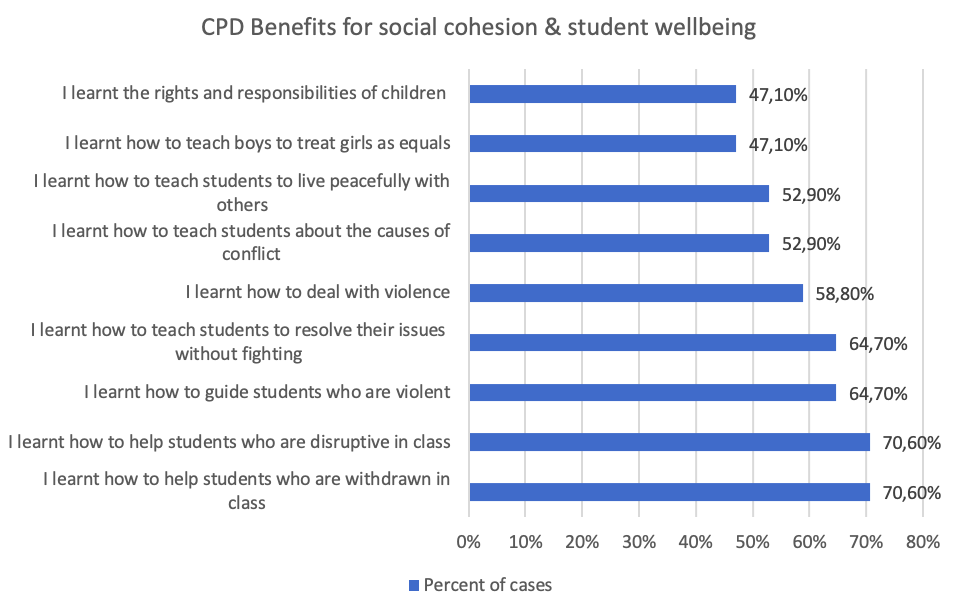

Teachers identified CPD benefits for helping learners who are withdrawn and disruptive in class (see Figure 5 below). However, the dimensions related to teaching boys how to treat girls equally and supporting learners to live peacefully were selected less as benefits of training attended. So while social cohesion was an important dimension of training support for teachers, its potential to help teachers deal with aspects of conflict and gender equity in the classroom still needs more exploration, systematic support and deliberate planning.

Figure 5: CPD benefits for social cohesion & student wellbeing

Teachers desired more sustained support and focussed training for skill and knowledge development to ensure their teaching practices address learning needs in an equitable manner. This is highlighted in the teacher responses below.

Trainings for … how we [should] deal with learners with difficulties is important in my view and it is missing. More specifically dealing with children that went through troubles and wars, those who survived rape and those with personal traumas that caused family conflicts…I believe I need that kind of training. (School 9, Maths teacher interview, 2019-2020)

Trainings for issues … of how should [we deal] with learners with difficulties is important in my view and it is missing. More specifically dealing with children that went through troubles and wars, those who survived rapes and those with personal traumas that caused family conflicts. I believe I need that kind of trainings. (School 9, Maths teacher interview, 2019-2020)

Another important dimension for ensuring equity which emerged from head teacher responses concerned matters of governance and training delivery. Specifically, responses indicated a desire for training consultations, increased interactions with governance actors and decision makers, and more equitable provisioning of the CPD itself. This is evident from teacher responses below.

Training is very important to all of us, because everyday something new is emerging. Therefore, we would like the education stakeholders to 1) increase the number of trainings, 2) provide training based on Somali culture and life, and 3) the school takes part in the process of identifying which type of training is needed and who needs to receive them. (School 3, Head teacher interview, 2019-2020)

The NGOs do not consult with us about which training we require, and we are instructed to take such training. But it would be better to consult with us.… (School 8, Head teacher interview,2019-2020)

In contexts of fragility, CPD also helps teachers assuage their own trauma. Psycho-social support is essential. However, our study indicates that this was inadequate for the teachers we surveyed.

- Reflections

Our intention has been to explore recent studies of teaching and learning experiences in IDP schools. Using a broadened notion of ‘quality education’ to include affective dimensions of learning and teaching alongside the cognitive, we focused on aspects of social cohesion in relation to teacher beliefs, teaching practices and professional development experiences.

Our argument, based on our findings, is that the ‘triple nexus’ approach to education in post-conflict, fragile contexts which regards teachers as key actors needs to better understand teacher beliefs, teaching experiences and professional development opportunities in these contexts. As teachers are themselves products of the surrounding fragility while serving as agents of social cohesion in conflict, our data highlights significant gaps in professional support and development opportunities for teachers necessary to ensure socially cohesive and inclusive teaching practices. Though the teachers expressed positive beliefs relevant to social cohesion and equitable teaching, we found that material challenges of teaching significantly inhibited the design of active and inclusive learning experiences.

Holistic CPD opportunities which consistently addressed teachers’ own needs for psycho-social support were unavailable. CPD training did not apply a positive disposition to social cohesion for teachers to engage critically with some of their negative beliefs of gender inequity and corporal punishment. We argue for more in-depth studies of existing CPD provisions for teachers in contexts of fragility.

If an inclusive understanding of quality and socially-just education are to be met, as promoted in the SDGs and by advocates of the triple nexus approach, it is imperative to prioritise efforts for sustained engagement with the complex needs involved in the professional development of teachers so they can confront and engage with their beliefs and, even more practically, translate their beliefs into classroom practices.

Co-authors: Yusuf Sayed, Ashika Sharma, Ali Bihi Hanaf, Muctar Hersi, Bang Chuol, Jal Paul and Massimo Alone

[1] World Bank Group (2017) Forcibly displaced : Toward a Development Approacj Supporting Refugees, the Internally Displaced and Their Hosts (Accessed 25 Aug 2022; Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25016

[2] UNICEF & IDMC (2019) Equitable access to quality education for displaced children. https://www.unicef.org/reports/equitable-access-quality-education-internally-displaced-children

[3] World Bank Group (2017) Forcibly displaced : Toward a Development Approacj Supporting Refugees, the Internally Displaced and Their Hosts (Accessed 25 Aug 2022; Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25016

[4]Mary Mendenhall UNICEF Education Think Piece series: Navigating the humanitarian-development nexus in forced displacement contexts (2019).

[5] UNICEF & IDMC (2019). Equitable access to quality education for displaced children. https://www.unicef.org/reports/equitable-access-quality-education-internally-displaced-children

[6] UNICEF & IDMC (2019). Equitable access to quality education for displaced children. https://www.unicef.org/reports/equitable-access-quality-education-internally-displaced-children

[7] “Paper commissioned for the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report, Inclusion and education”.

[8] Plan International (PI) in partnership with the University of Sussex (Centre for International Education), Gambella University, and the Puntland Development Research Center, as one of the four consortia of the BRiCE programme, engaged in research about teacher and learner experiences of access to quality education in Ethiopia and Somalia. The research focused on the dynamics of education provision and delivery for refugees in Ethiopia and internally displaced children in Somalia, exploring the role of quality education in relation to the humanitarian-development nexus in conflict-affected contexts to understand the ‘triple nexus’ in such contexts.

[9] UNHCR (2019). Operational Update Somalia. Available at: file:///C:/Users/Acer/Downloads/UNHCR%20Somalia%20-%20Operational%20Update%20October%202019.pdf & https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/cccm_somalia

[10] https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/cccm_somalia

[11] Lindley, A. (2013). Displacement in contested places: governance, movement and settlement in the Somali territories. J. East. Afr. Stud. 7, 291–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2013.776277

[12] Puntland State of Somalia, Ministry of Education and Higher Education (2017). Global Partnership for Education Programme Development 2017-2020. Available at: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/program-document-gpe-grant-puntland-2017-2020-somalia (Accessed 15.10.2021)

[13] Federal Government of Somalia (2019). Aid Flows in Somalia.

[14] Geoghegan, P. (2021). UK government accused of ‘grotesque betrayal’ as full foreign aid cuts revealed. openDemocracy