AI in Education and Research: Towards a More Ethical Engagement

In this blogpost, which is a cross-posting with the Global Challenges dossier on the futures of universities (#14) published in November 2023, Moira Faul and Anna Hopkins argue that AI is based on extractive and exploitative origins and practices and requires a more ethical engagement.

There is a large amount of public writing about the promise of artificial intelligence (AI) for supporting social inclusion, freeing up researchers from grunt work and the “top x AI tools for teachers”. What is less well understood is where “AI” comes from and whose oppression is needed for it to succeed. In the case of AI and education that interests us here, we will show what is at stake in these seemingly user-friendly AI interfaces by answering three interrelated questions about large language models (LLMs) and algorithms.

1. What lies behind AI?

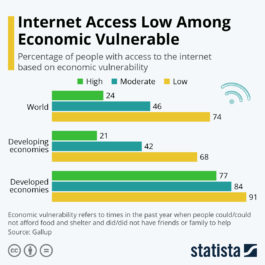

Percentage of people with access to the internet based on economic vulnerability. The fact that a majority of human beings are not represented on the internet, as denounced by Moira Faul and Anna Numa Hopkins, goes hand in hand with the fact that a majority of human beings do not have access to the internet.

Source: Statista.

AI relies on datasets scraped from the internet in large language models (LLMs) and algorithms (which are just sets of rules to be followed in calculations). These large – but narrow – datasets encode the values of privileged members of WEIRD (Western/White, educated/English-speaking, industrialised, rich, democratic) societies who design them and profit from them. A minority of humanity is represented on the web; the majority is not.

Students cannot give consent to their data being profited from by platforms that are mandated by their institutions. Moreover, the contribution of African scientists who collected data during the 2020 Covid pandemic was not recognised even as their data were analysed to benefit us all. How do we break with practices of coloniality where raw materials – now data – are extracted and sent to distant elites for value-added manufacture?

AI is also environmentally extractive since the data centres hosting LLMs require enormous amounts of electricity and water for cooling, diverted from humans and places that need it. AI tools reinforce and promulgate dominant epistemologies, further marginalising other ways of knowing and doing. Datafication introduces new actors – digital platforms – as powerful intermediaries in educational processes and decision making. Recent advances appear to owe more to business practices than technical breakthroughs. What research agendas can investigate these new education actors and their opaque value creation models and motivations?

Your open access or pirated articles and books are fodder for LLMs, but you will not be cited. “CAPTCHAs” on websites identify you as a human, and also train LLMs. Voluntary human efforts to produce public goods are reused without permission to generate profits as well as answers to your questions. Even more exploitative are the working conditions of data workers in low-income countries without whom AI tools would not be marketable to schools. AI needs HI (human intelligence) to nudge it – but in which direction?

2. What is data used for and with what effects?

Historical and contemporary biases are captured by data, encoded in LLMs, and perpetuated by algorithmic outputs. This matters since AI is used in selection decisions for colleges and jobs, and to monitor humans in work, exams and society, despite evidence of significant failures and injustices built in to these systems.

LLMs generate a silicon ceiling – an imperceptible, but systemic, barrier to opportunity for marginalised peoples – through biased algorithmic decision making. AI facial recognition systematically misidentified Black women but not White men, and ChatGPT predicted “terrorist” as the word to follow “Muslim” in 23% of test cases. AI replicates, reinforces and exacerbates historical disadvantages and human biases under a veneer of objectivity and scientificity. Actual harms now are as much existential threats to marginalised people as future harms are to us all.

AI benefits those who resemble its techno-optimistic, corporate designers. It is not by chance that most of the research in these hyperlinks is produced by people who do not.

3. How to move towards more ethical engagement with AI?

- Move from values based on extraction and exploitation towards values more usually found in education (ethics of care) and research (informed consent, precautions against causing harm).

- Centre humans – and education and research – and then consider how technologies support human flourishing for “tech on our terms”.

- Urgently address AI governance to redress existing inequalities and regulate how technology industries structure human choices and make it harder to “click wisely”.

- Recognise the corporate origins and capture of AI narratives, purposes and governance.

- Teach age-appropriate digital literacy (and general literacy) to teachers and students without adding to teachers’ workload.

- Demand algorithmic transparency and ethical audits.

- Use language carefully: generative AI generates; it does not think, predict, decide or hallucinate.

- Change citation practices and institutional and funding incentives to avoid the “compound effect” of rewarding privileged groups and further marginalising others.

- “Imagine and craft the worlds you cannot live without, just as you dismantle the ones you cannot live within” (Ruha Benjamin).

Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence (UNESCO, 2022).

Drawing attention to issues that AI generates for education does not deny that digital technologies can, and might, be used for the common good. But we should not confuse corporate techno-optimism for human-centred AI use. Even if the genie is out of the bottle, it is still bound to it and can be put back in.

In November 2021, 193 states adopted UNESCO’s global standard on AI ethics. Governments, international organisations and the private sector could govern this technocosm in the common interest to overcome allocational and representational harms.

Using technology is as essentially human as ethics; let’s lead with ethics. Governance and regulation need to be based on the duties of decision makers to safeguard rights for humans, and ensure that human and planetary purposes guide algorithms.

Now that would be intelligent.

About the Authors:

Moira V. Faul

Senior Lecturer, Geneva Graduate Institute

Executive Director of NORRAG, a research centre of the Geneva Graduate Institute

Anna Numa Hopkins

Policy Engagement Lead, NORRAG

Further reading from NORRAG:

Education, AI and digital inequities

Education, technology and private sector actors: towards a research agenda

Policy Insights: The Digitalisation of Education

Digitalisation of Education Blog Series

A resource list for tackling coloniality and digital neocolonialism in EdTech

FreshEd Podcast: Generative AI in Education (ChatGPT)